The Year That Changed The World

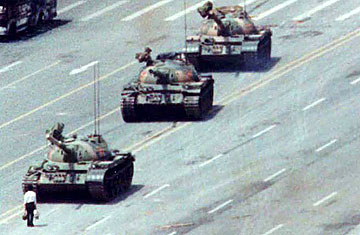

If you think you're sometimes spoiled for choice, consider the lot of a news editor on the first weekend of June 1989. On the afternoon of Saturday, June 3, the condition of Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of Iran, began to rapidly deteriorate. Just before midnight, Khomeini, 86, died, his death announced on the radio a few hours later. Tehran is 31/2 hours behind Beijing, so at just the time the crowds in Iran were taking to the streets in extraordinary expressions of grief, the people of Beijing, no less in shock, were coming to terms with what had happened in the early hours of that Sunday morning. Troops of the People's Liberation Army had cleared the remnants of student protests in Tiananmen Square, shooting into the crowds as they did so.

But that was not all. As grief and horror respectively gripped Tehran and Beijing, Poles were awakening to a day of hope. In the spring, Poland's ruling Communist Party had been compelled to open roundtable talks with the opposition, including representatives of Solidarity, the civic and trade-union group that had survived the imposition of martial law in 1981. In Hungary in 1956, and again in Czechoslovakia in 1968, Soviet tanks had crushed popular reform movements. By 1989, however, the winds of change in Eastern Europe had reached gale force. In the Soviet Union itself, the General Secretary of the Communist Party, Mikhail Gorbachev, was discarding old habits like a teenager throwing out last year's fashions. The Soviet leadership no longer had the stony heart or iron fist to impose its rule by force of arms. And so on June 4, Poland was to hold an election, albeit one in which the Communist Party's position was protected. When the two rounds of votes were counted, Solidarity had won virtually every seat in the Sejm, Poland's parliament, that it could contest. The division that had scarred Europe since the end of World War II was coming to end. The rivets in the Iron Curtain were beginning to pop.

All Changed

Historians, picking over what has gone before, revising past judgments, will tell you that our understanding of the past is never final. What were thought to be world-changing events dim into topics of an obscure Ph.D. thesis; what seemed to be small stories turn out to be the ones that shaped the future. All is relative.

Yet 1989 truly was one of those years that the world shifted on its pivot. Some things did change, and changed utterly; we are living with their consequences still. Some things ended, too — not just communism as a state practice, for example, but also the idea that the international system is driven solely by state action. In a way that was only dimly perceived 20 years ago, elements such as multinational business, technological innovation and personal faith now shape our world just as states do.

Whatever the importance of events after 1989, the year itself is one for the ages. That was understood at the time. In the most famous contemporary analysis of current events, Francis Fukuyama, a brilliant American scholar who was then serving on the policy-planning staff of the U.S. State Department, published an essay in the journal the National Interest entitled "The End of History." The statement of his central thesis was unequivocal: "What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government." (Fukuyama turned the article into a book, and over the years, in a spirit of generous intellectual openness, defended and refined his thesis in the light of the many attacks on it.)

In history's hourglass, 20 years amounts to just a dribble of sand. It is still too early to know if Fukuyama's claims will be fully borne out. As I write this, the world is transfixed by the events in Iran, a state that hardly rated a glancing reference in Fukuyama's original article. But one aspect of Fukuyama's thesis has been proven right in spades. Notwithstanding the fact that the world economy is in the midst of the most severe contraction since the 1930s, there really has been "an unabashed victory of economic liberalism" over a competing economic system — that of a centrally planned economy — which once appeared to offer an alternative to free markets.